The Longer You Can Look Back, The Farther You Can Look Forward

2020

Courtesy of Sabrina Amrani Gallery, Madrid

The Longer You Can Look Back, The Farther You Can Look Forward critically explores the influence of image culture and propaganda, examining how visual manipulation shapes public perception and political narratives across history. Through references to Brechtian theatre, Goebbels' propaganda, and the performative gestures of figures like Churchill and Mao, the project reveals how visual tropes perpetuate political influence. Techniques of anamorphosis, associative imagery, and disorienting spatial interventions challenge viewers to question their role within the machinery of image production and consumption. By transforming images into sites of cultural memory and ideological reflection, The Longer You Can Look Back, The Farther You Can Look Forward invites a necessary skepticism toward the narratives visual media enforces.

If You Are Going Through Hell, Keep Going. Churchill. (panel I)

(2017–2019)

Inkjet on vinyl

12’ x 8’

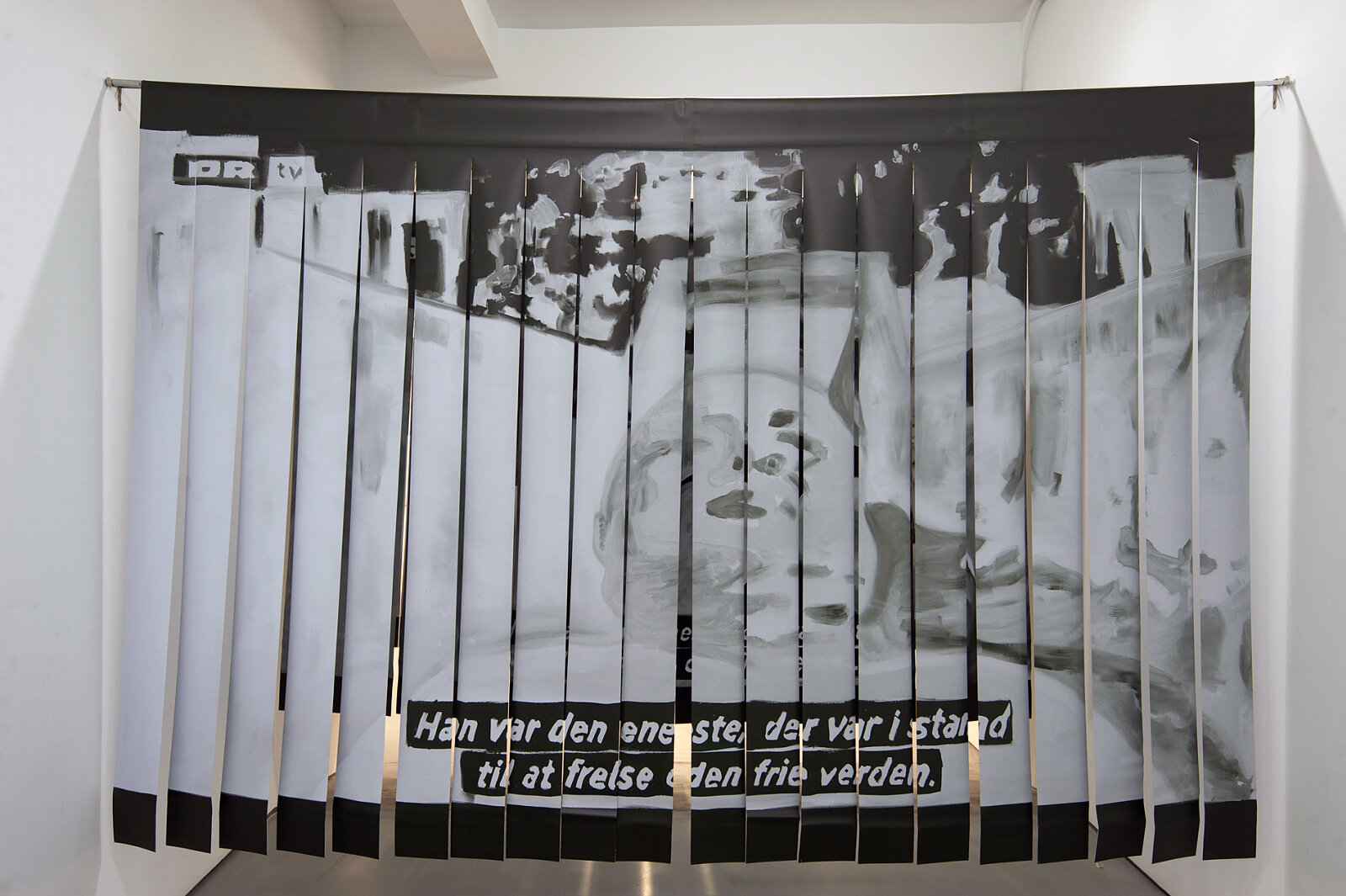

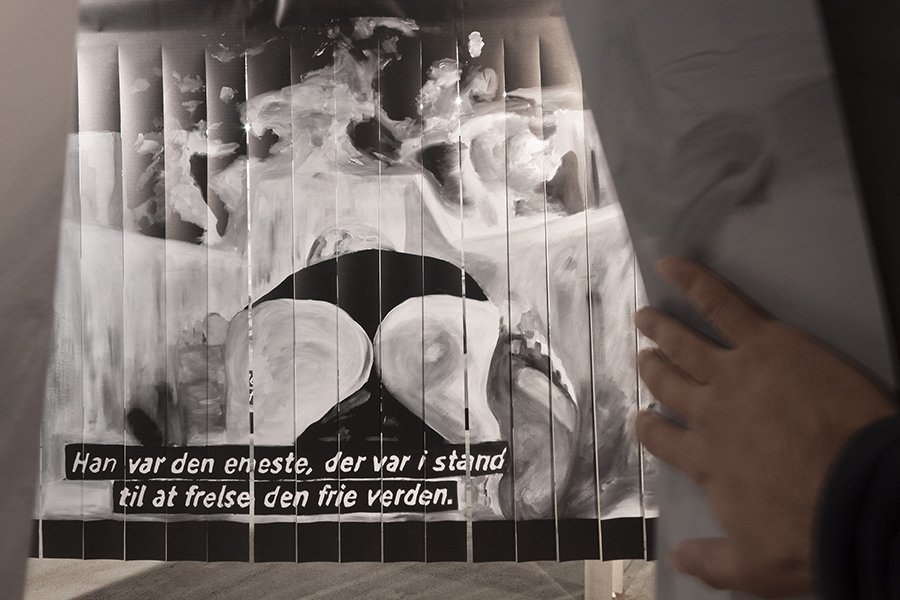

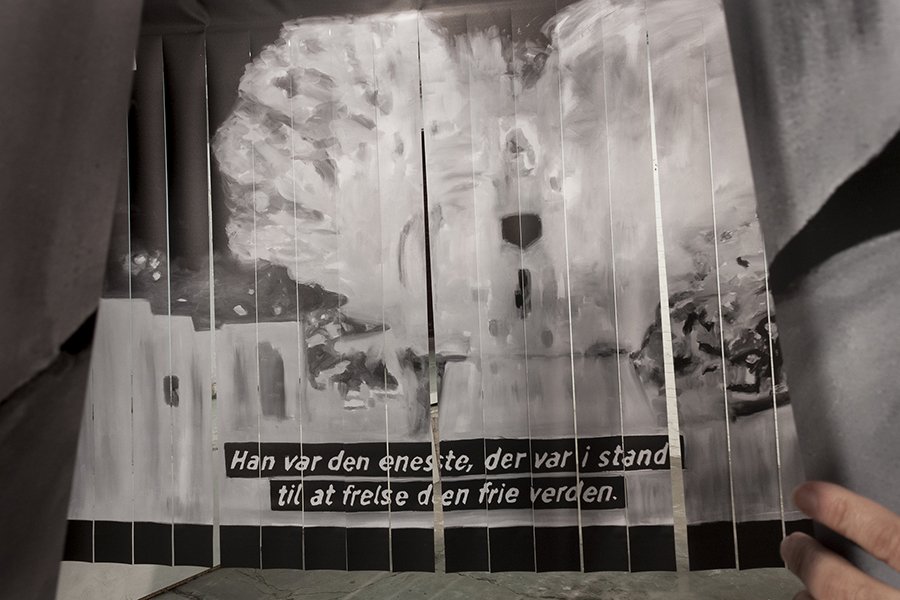

If You Are Going Through Hell, Keep Going. (Churchill) functions as both a conceptual and physical gateway, positioning viewers to confront the interplay of propaganda and persona construction from the outset. Installed as the entry piece, this triptych vinyl print—derived from documentary stills of Winston Churchill sliding headfirst down a waterslide in the south of France—transforms a playful moment into a curated image of resilience and approachability, signaling the construction of personal myth even in leisure.

By requiring viewers to pass through Churchill’s carefully crafted persona, the installation underscores the serialized nature of propaganda and sets the exhibition’s thematic tone. If You Are Going Through Hell, Keep Going. (Churchill) thus serves as both threshold and thesis, framing an exploration of political influence and the enduring power of visual mythology within the public sphere.

If You Are Going Through Hell, Keep Going. Churchill. (panel II)

(2017–2019)

Inkjet on vinyl

12’ x 8’

If You Are Going Through Hell, Keep Going. Churchill. (panel III)

(2017–2019)

Inkjet on vinyl

12’ x 8’

Amusement Park, 1926

2020

Lead oil on canvas, hand-carved wooden frame

40” x 46” x 4”

Amusement Park 1926 probes the unsettling intersection of nostalgia, violence, and betrayed innocence. At first glance, the work appears as a delicate, washed-out Impressionist rendering of a fairground, evoking a sentimental past. Closer inspection, however, reveals hooded KKK figures occupying the merry-go-round, disrupting any notion of innocence. Based on a 1926 photograph by Clinton Rolfe of a KKK amusement park in Colorado, the piece exposes disturbing layers of historical spectacle within American visual culture.

The ornate frame, echoing French colonial design and subtly incorporating nooses, heightens this tension, implicating symbols of beauty and brutality within cultural artifacts. Together, the painting and frame serve as a haunting reminder of the latent violence embedded in historical imagery, urging viewers to consider how memory and aesthetics contribute to the perpetuation of social trauma.

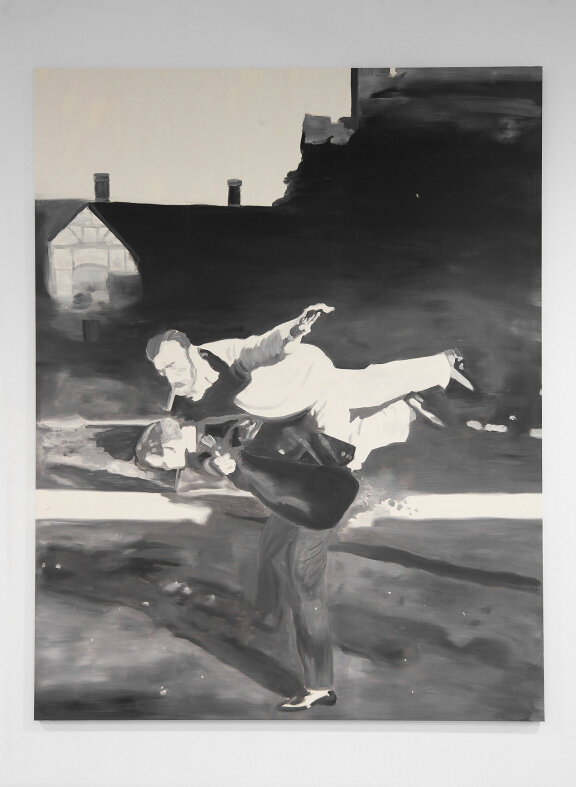

Drifters

2018

Lead-based oil on canvas

51” x 90”

Drifters exists as both a large oil painting and a monumental wallpaper of repeated images, examining the performative nature of political spectacle. Focusing on Chairman Mao’s 1966 propaganda swim in the Yangtze River—captured by the BBC to project strength amid criticism—the work reflects on how visual media amplifies and perpetuates constructed personas, a tactic echoed by figures like Vladimir Putin.

The repetition of Mao’s image as wallpaper underscores propaganda’s reach, interrogating how powerful figures shape public perception through image proliferation. Drifters compels viewers to confront the role of iconography in shaping political narratives, revealing how symbols drift across contexts to sustain ideological influence over time.

Sellers

2017

Lead oil on canvas, mp3 audio

Painting: 136” x 84”

Audio: 28 seconds

Selers explores the convergence of propaganda, marketing, and psychological influence through an installation featuring an anamorphic portrait of Joseph Goebbels and an accompanying sound piece. This work highlights ideological parallels between Goebbels, the Third Reich’s Minister of Propaganda, and Edward Bernays, the American public relations pioneer and nephew of Sigmund Freud, underscoring their impact on mass persuasion.

The audio component features Thea Rasche, a 1920s German pilot and media sensation whose fame, cultivated by Bernays, promoted consumer ideals like “self-expression” through dress. This interplay between propaganda and consumer culture is further complicated by Goebbels’s distorted portrait, shifting with the viewer’s position to emphasize the subjectivity inherent in ideological influence. Sellers thus reflects on how modern consumer culture is deeply rooted in propaganda’s psychological tactics, prompting critical awareness of the persuasive power embedded in media.

REHEARSAL

2019

Five channel video installation

6’ 30”

Rehearsal is a five-channel video installation that captures a five-act rehearsal featuring two contemporary dancers, choreographed in collaboration with Vancouver-based choreographer Emmalena Fredriksson. This work interprets a musical piece Bertolt Brecht composed for his early play, Mann ist Mann, performed in Berlin between 1924 and 1926. Brecht’s play humorously explores themes of war, human fungibility, and the erosion of identity through brainwashing and propaganda.

In Rehearsal, the dancers’ movements echo these themes, embodying the repetitive, mechanistic loss of self inherent in Brecht’s critique. The multi-channel setup amplifies the fragmented and cyclical nature of the performance, mirroring the dissolution of individuality within systems of power. Through this reinterpretation, Rehearsal becomes a meditation on identity under duress, exposing the fragile boundaries between autonomy and control in the face of ideological influence.

Descry! How Far Back Can You See?

2019

Silver infused porcelain

20” x 8” x 8”

Descry! How Far Back Can You See? challenges conventional self-perception by replacing a mirror’s focus on self-image with a wide-angle view of surroundings, captured in silver-infused porcelain cylinders. This reversed perspective shifts attention from the viewer to the space and history behind them, displacing the self within the curved surface.

By transforming reflection into a device for perceiving the past, Descry! prompts viewers to reconsider their position in time and space, inviting a layered exploration of memory and perception as it unfolds in real-time.

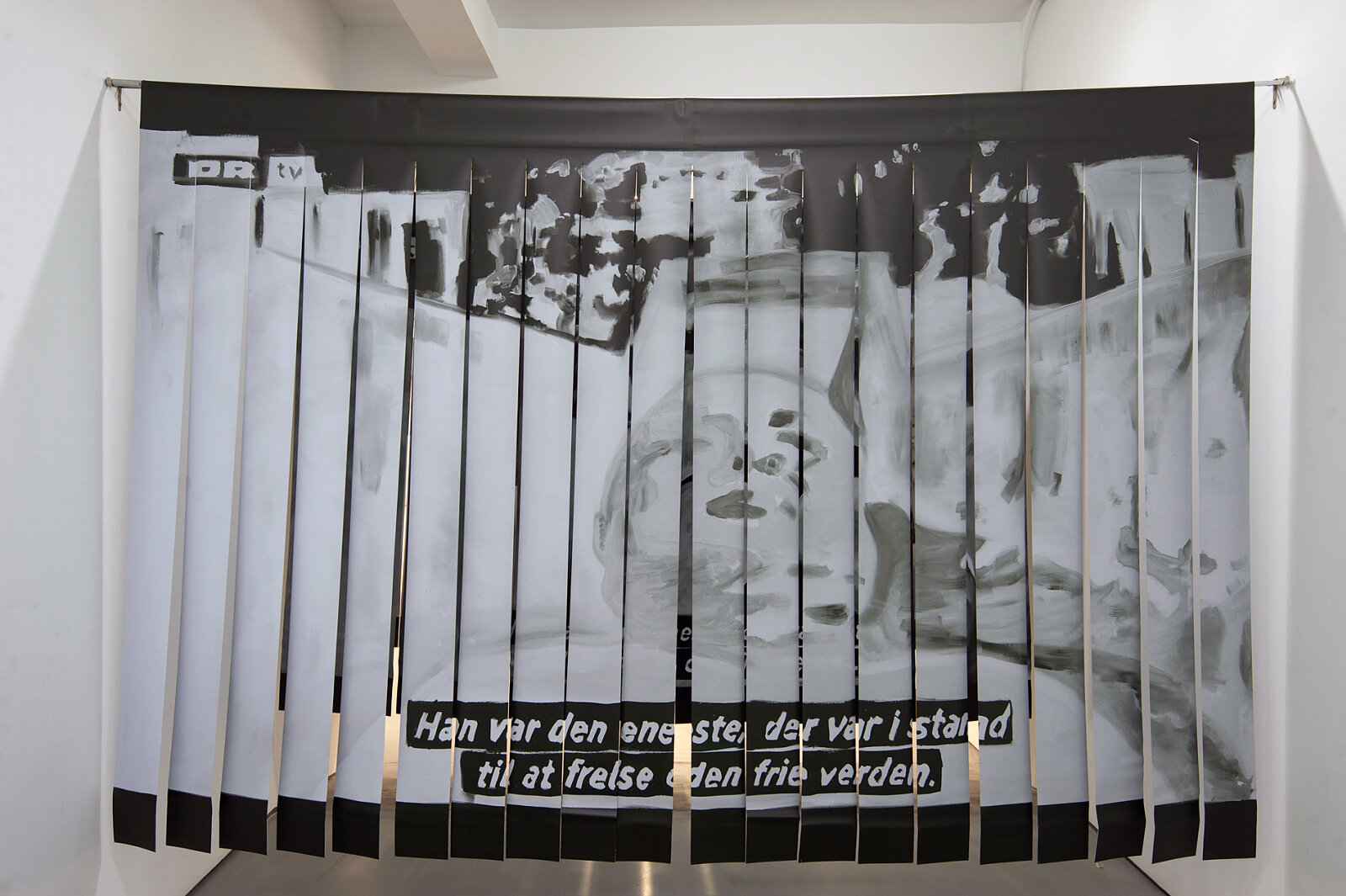

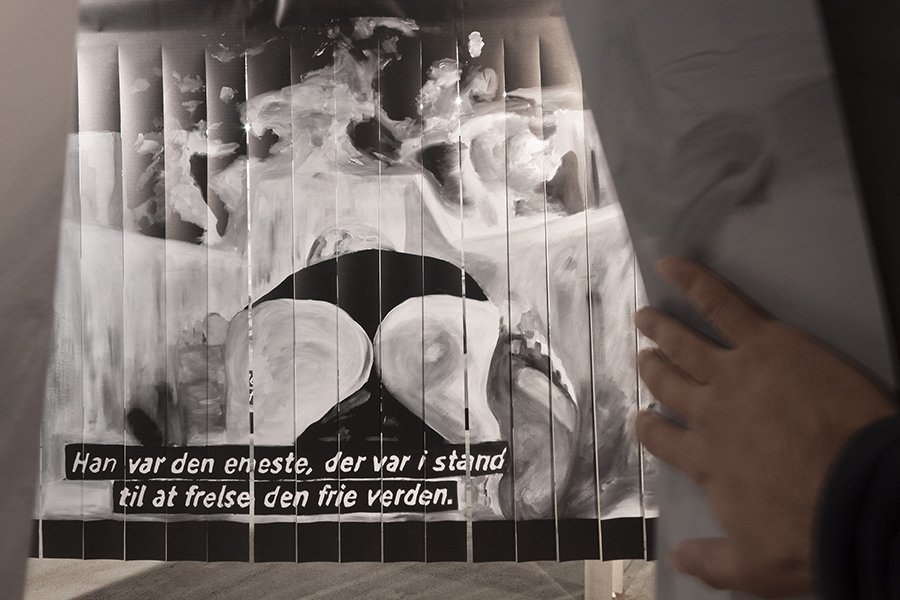

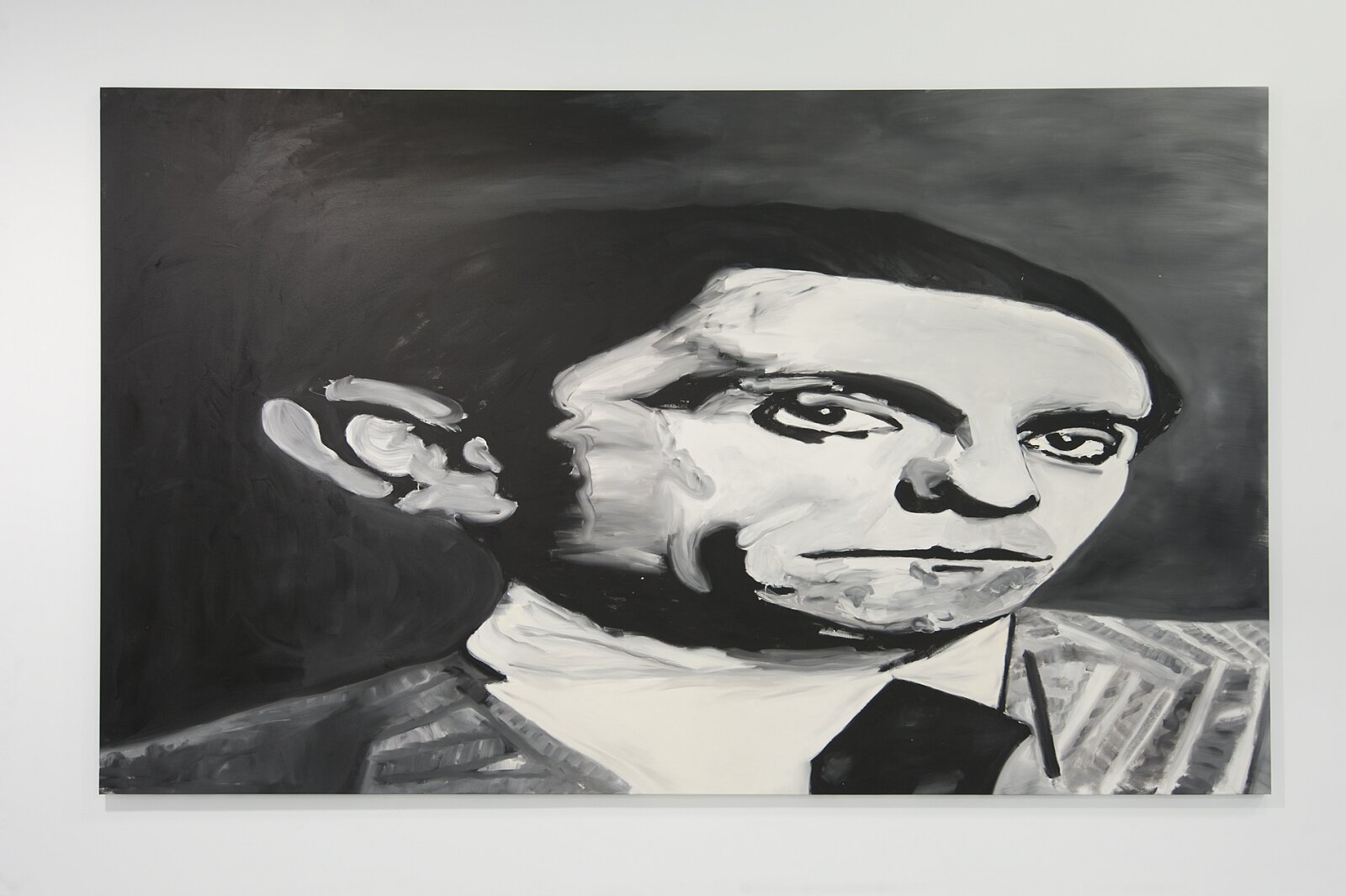

Mann Ist Mann

2017-2019

Lead oil on canvas

84” x 124”

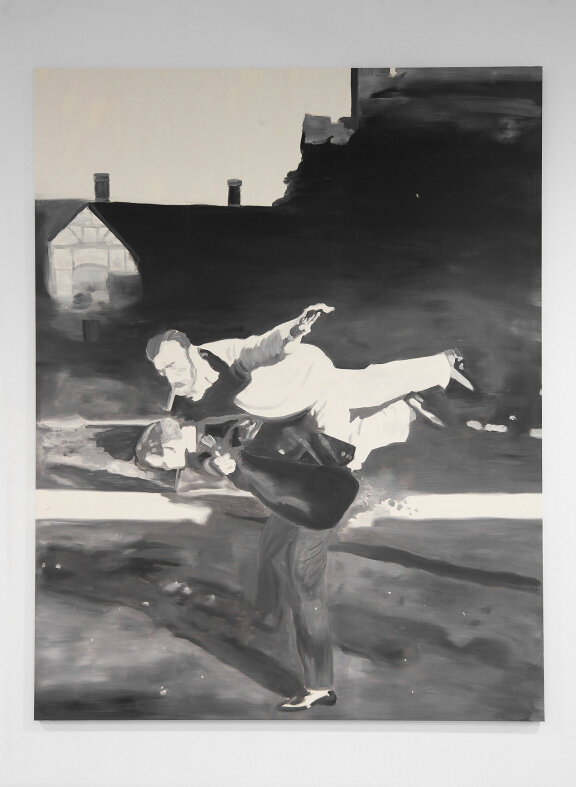

In Mann Ist Mann, the title—meaning “a man is a man”—reflects Brecht’s concept of individuals as interchangeable within ideological systems, particularly in military or authoritarian contexts. This idea resonates through the painting’s depiction of Tsar Nicholas II and Prince Nicholas of Greece in a staged moment of playfulness, paralleled with the modern political dynamics of Vladimir Putin and his advisor Vladislav Surkov.

Surkov, a former theatre director influenced by Brechtian techniques, has used Epic Theatre’s strategies to craft a controlled, self-aware narrative around Putin’s authority. The Tsar’s direct gaze breaks the “fourth wall,” echoing Brecht’s intent to reveal the constructed nature of power—a nod to Surkov’s manipulation of public perception through performance and irony.

By juxtaposing figures across history, Mann Ist Mann critiques the performative aspects of authority, suggesting that power relies as much on image and manipulation as on influence. The work transforms a playful historical moment into a reflection on how leaders are crafted as symbols within systems that ultimately render them replaceable, engaging with Brecht’s enduring ideas on the theatricality of power.

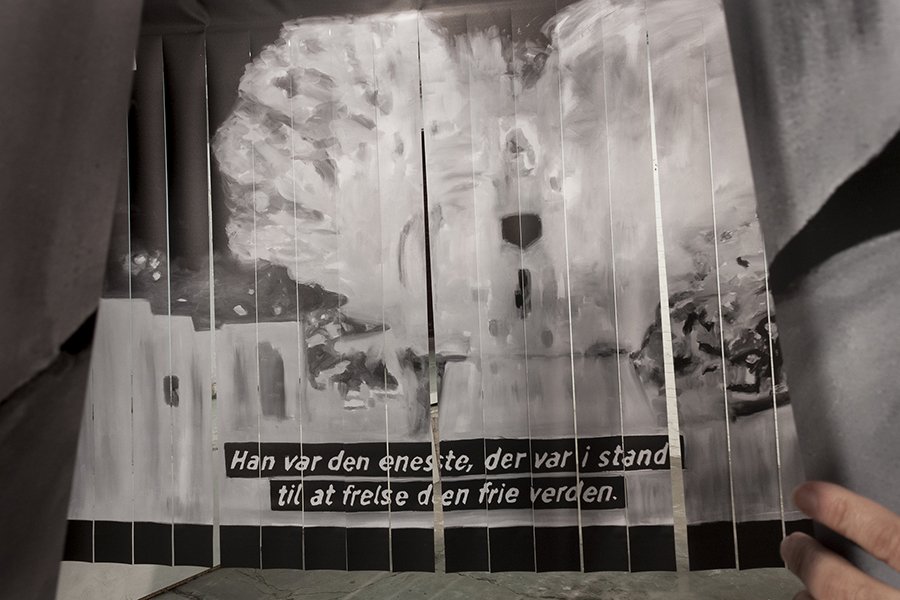

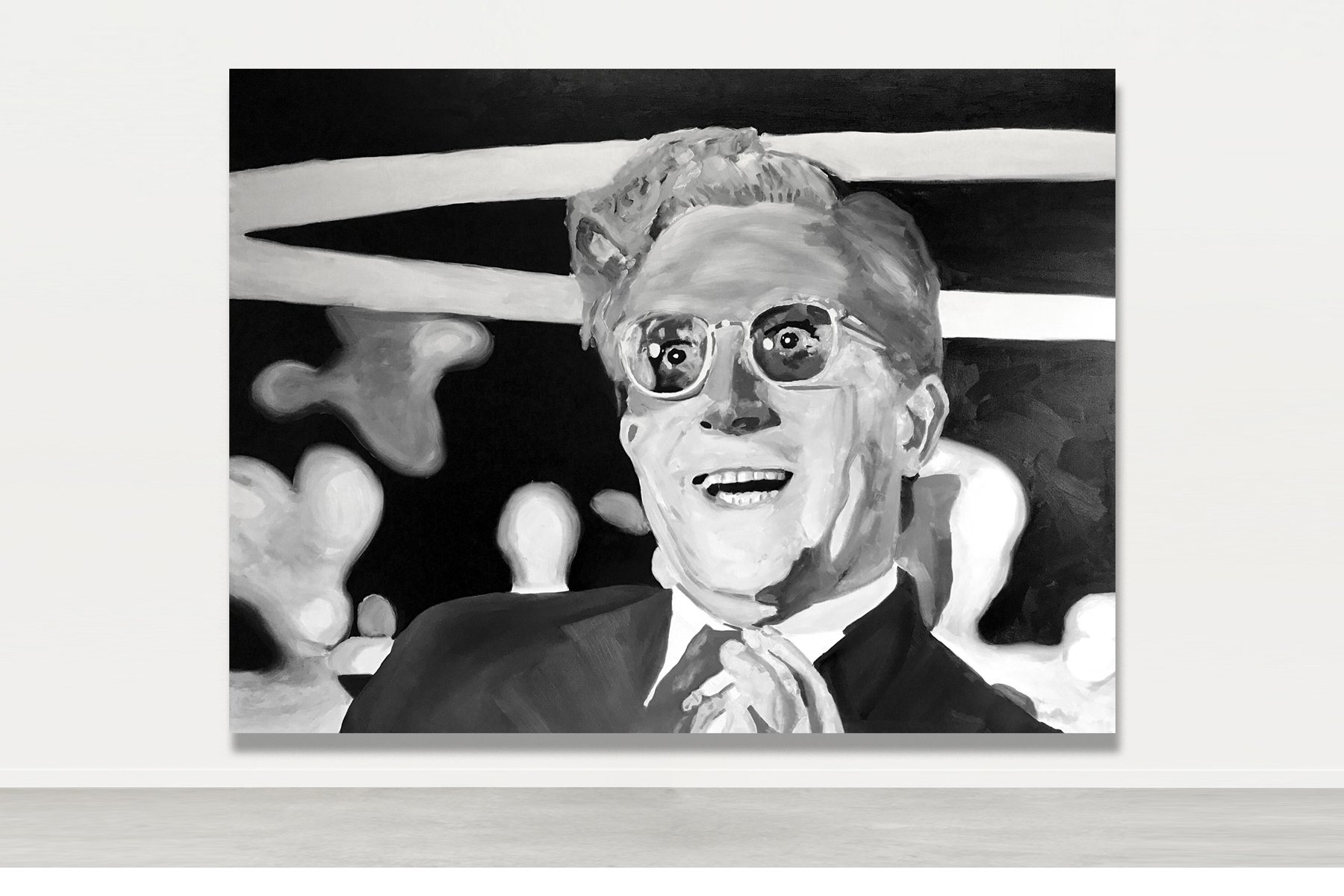

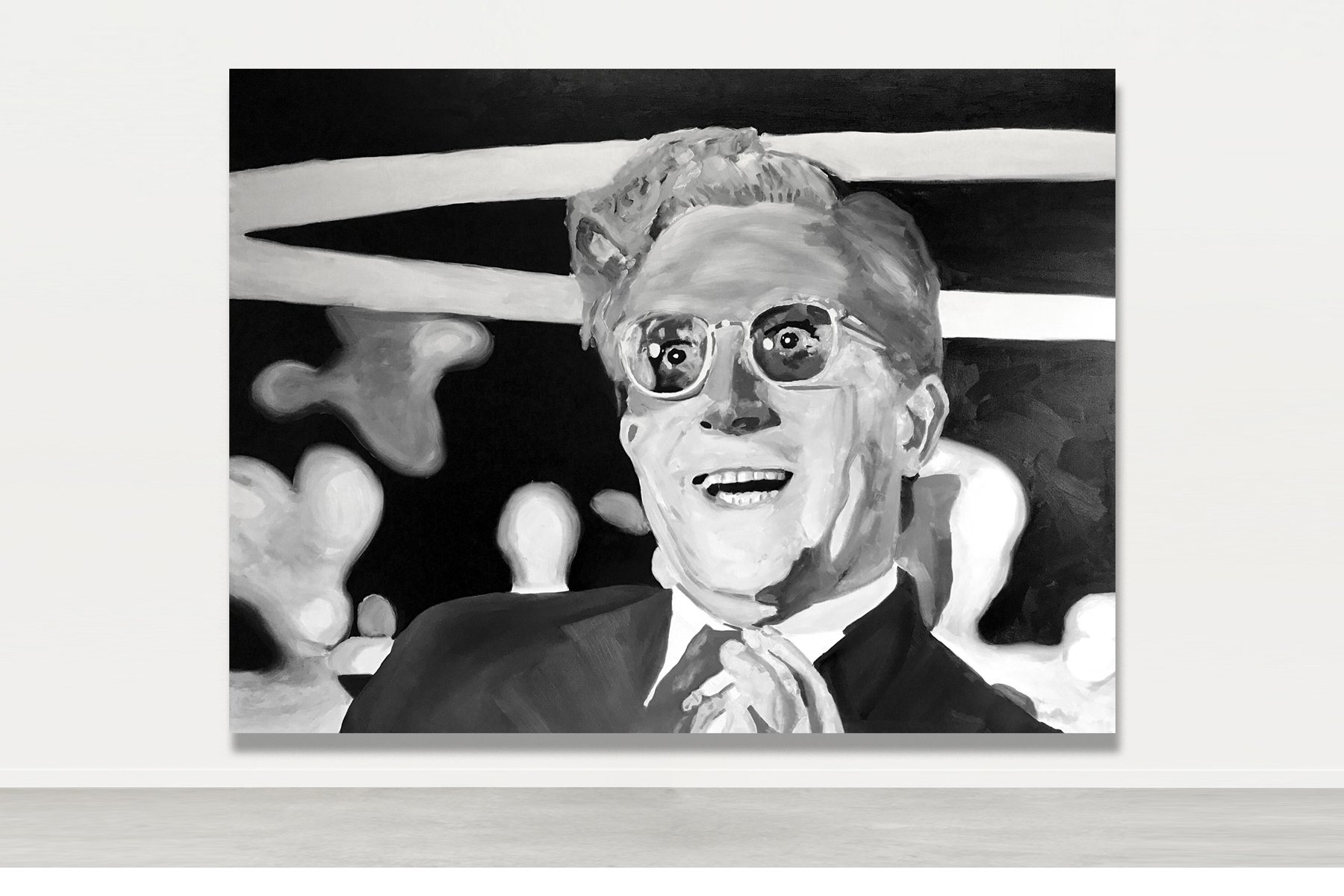

The Man Who Sold The World

2017

136 × 84”

Lead oil on canvas

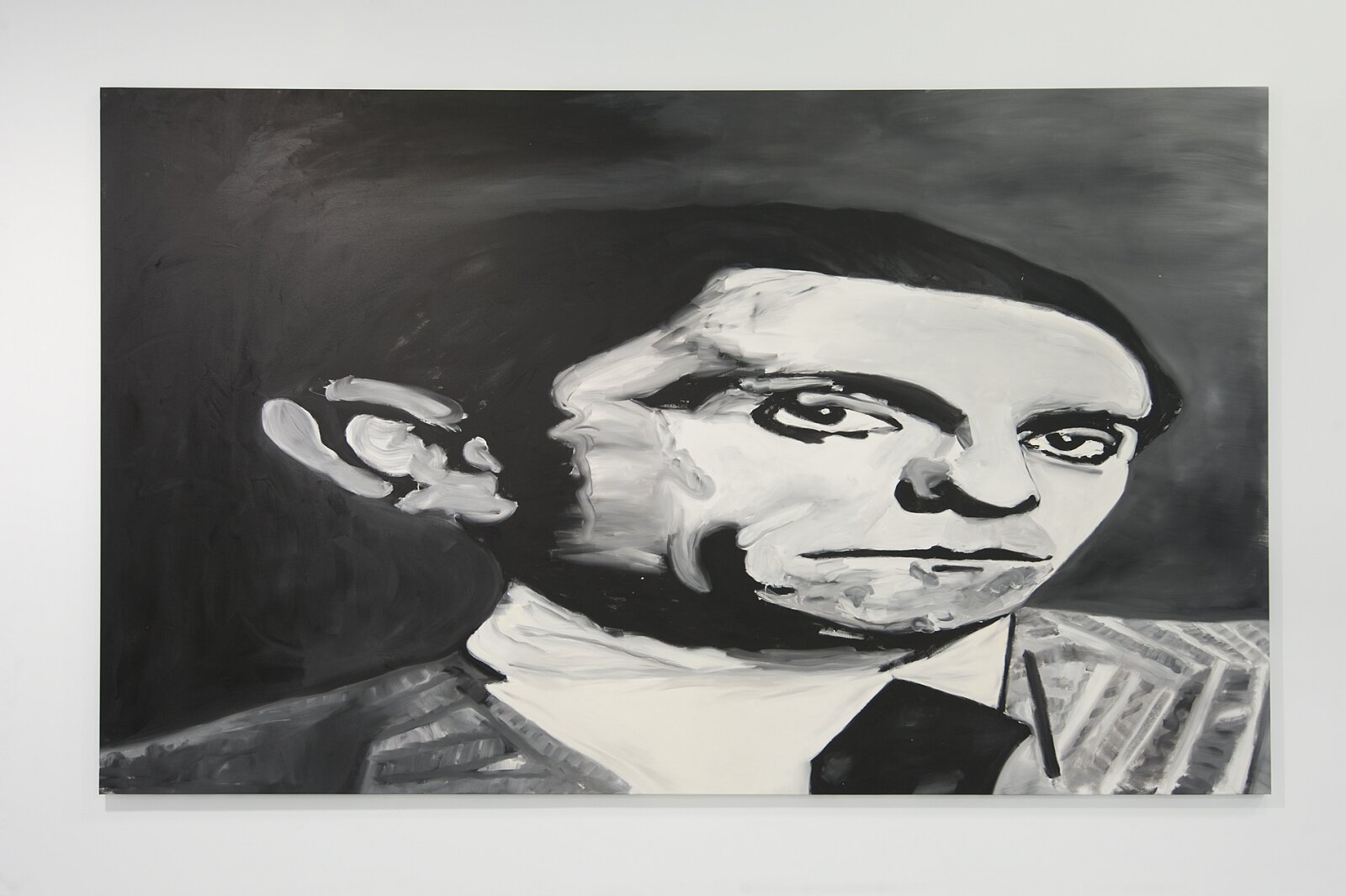

The Man Who Sold The World (2017) presents Stanley Kubric’s Dr. Strangelove played by Peter Sellers, his figure monumental and charged with tension, caught in the moment before his infamous involuntary Nazi salute. Painted in lead oil on canvas at a dramatic scale, the painting amplifies the neurosis of men in power, where control and collapse are inseparable. Strangelove’s expression—part exhilaration, part struggle for restraint—is frozen in a state of contradiction: a mind devoted to cold logic, yet overtaken by unconscious ideological impulse.

Detached from the cinematic frame, the painting repositions this figure in the realm of contemporary politics, where the performance of authority has become indistinguishable from le théâtre de l’absurde. In its weight, surface and material presence, the work extends beyond Kubrick’s satire, transforming Strangelove from a Cold War relic into a specter of power’s enduring pathology. What emerges is not just a historical reference, but a meditation on how the theater of political control continues to play out—its absurdities, contradictions and self-destructive instincts laid bare.