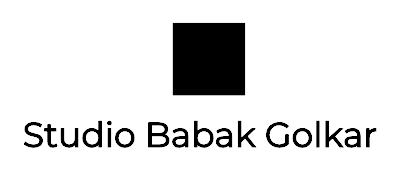

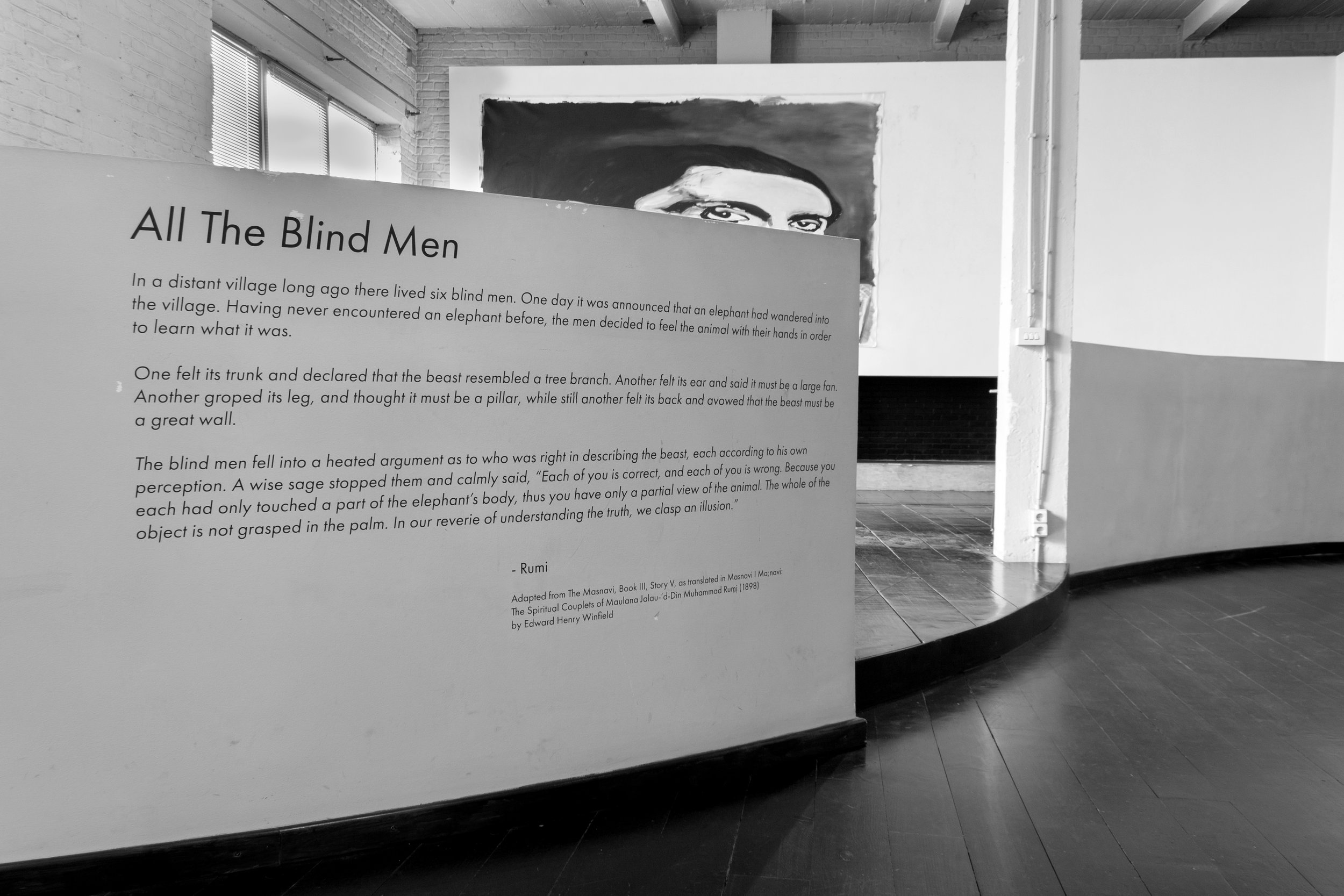

All The Blind Men, 2019

Servais Family Collection, Brussels in partnership with the Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver.

All the Blind Men investigates the fractured nature of truth and the ideological mechanisms that shape perception, history and collective memory. Painting functions as both a material practice and a conceptual apparatus, interrogating how images mediate, replicate,and distort historical narratives. Fragmentation, deconstruction and destabilized forms challenge the presumed stability of representation, exposing the ways in which truth is selectively constructed and imposed.

In an era where media, technology and institutional power dictate public consciousness, All the Blind Men critiques the mechanisms by which narratives are shaped and sustained. By unsettling the authority of images and the systems that produce them, the work reveals the instability of perception itself. A space of rupture emerges, where the act of looking becomes a confrontation with the structures that frame understanding.

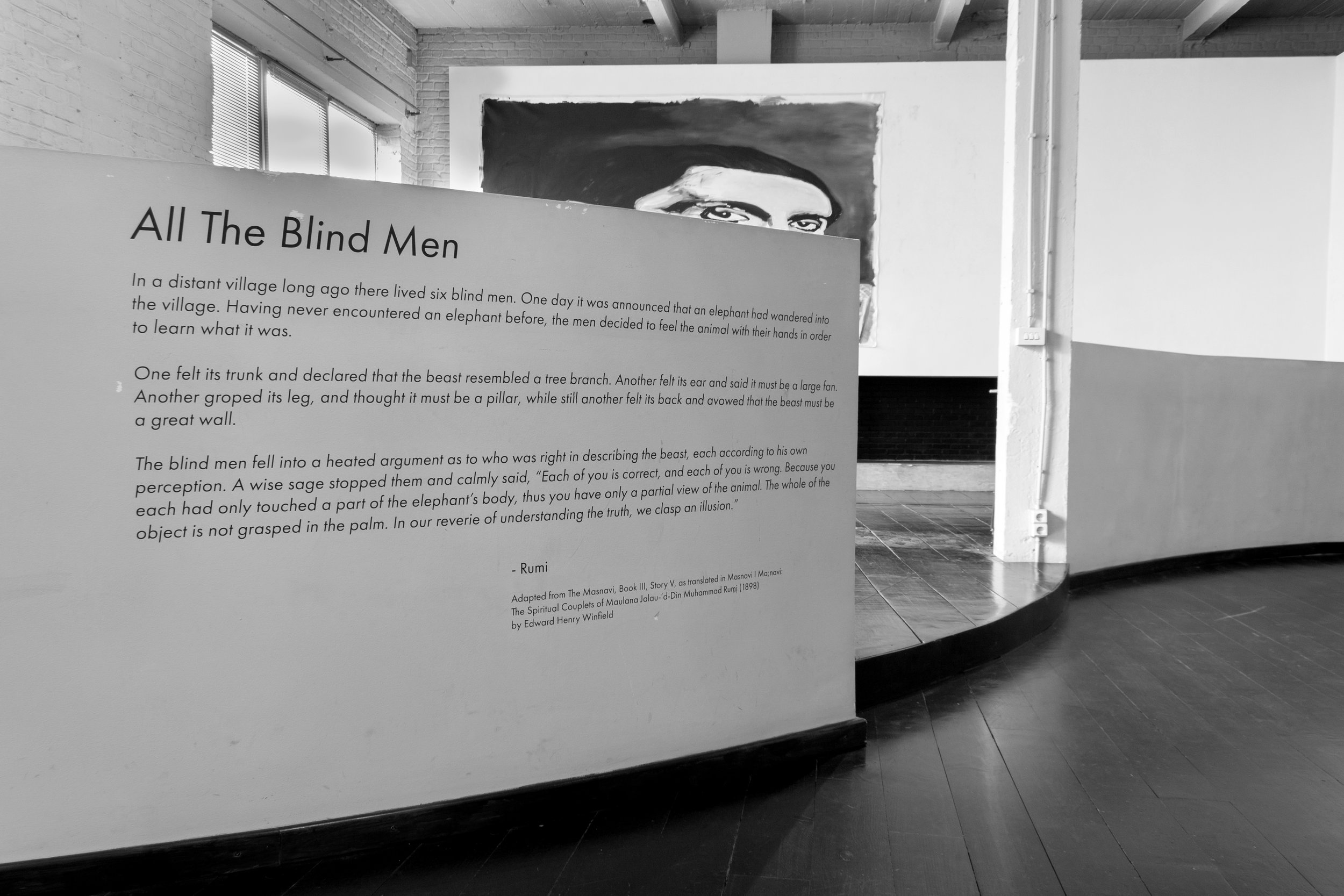

“If You Are Going Through Hell, Keep Going.” Churchill, 2017-2019

Inkjet on vinyl

120” x 84”

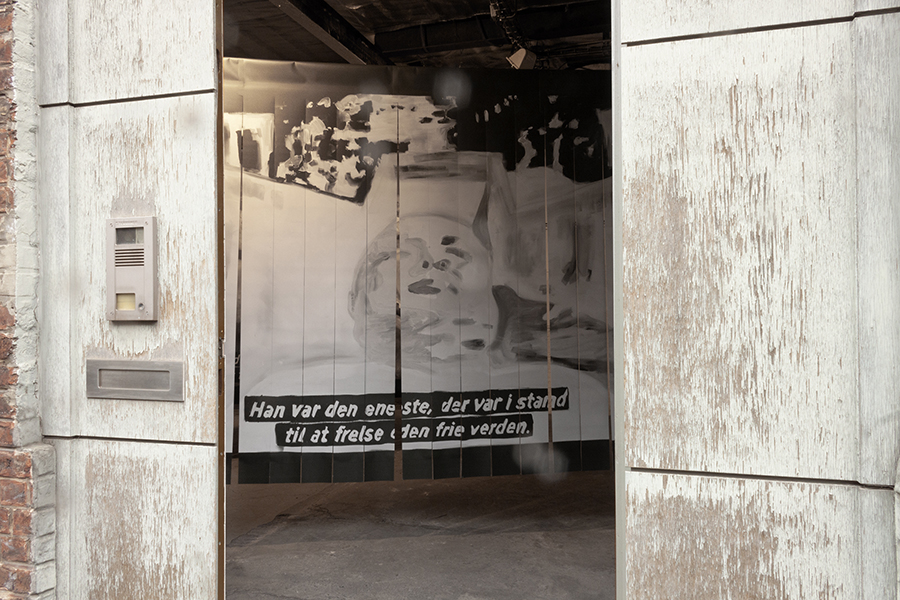

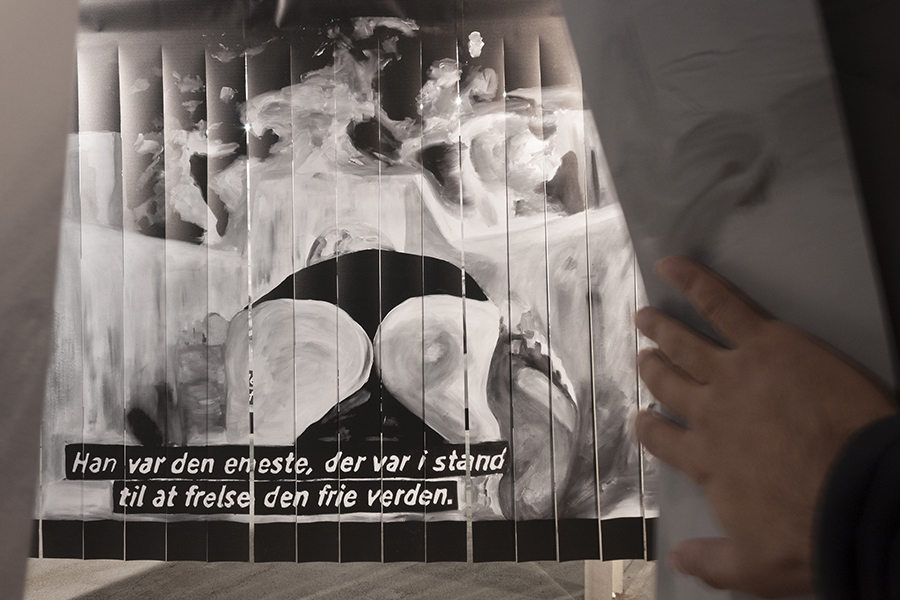

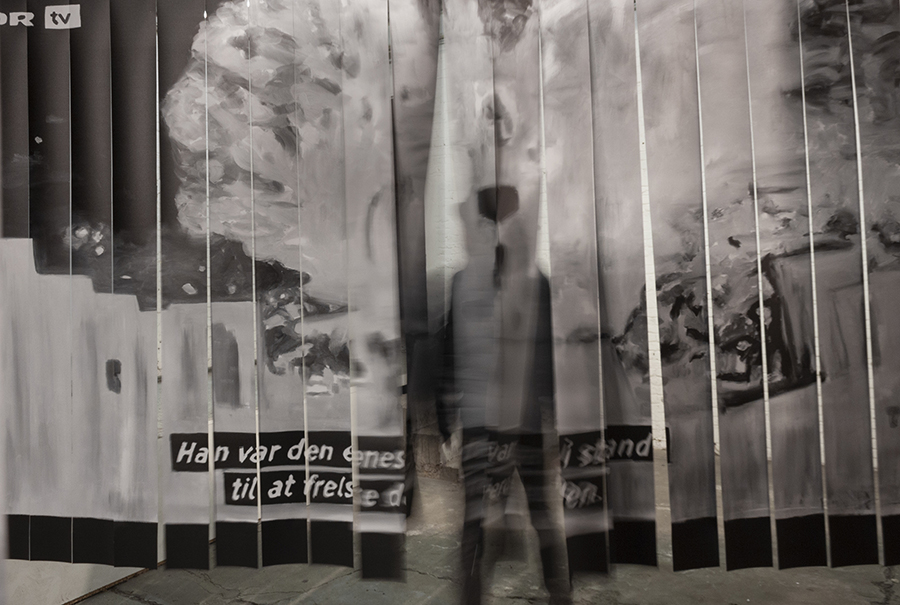

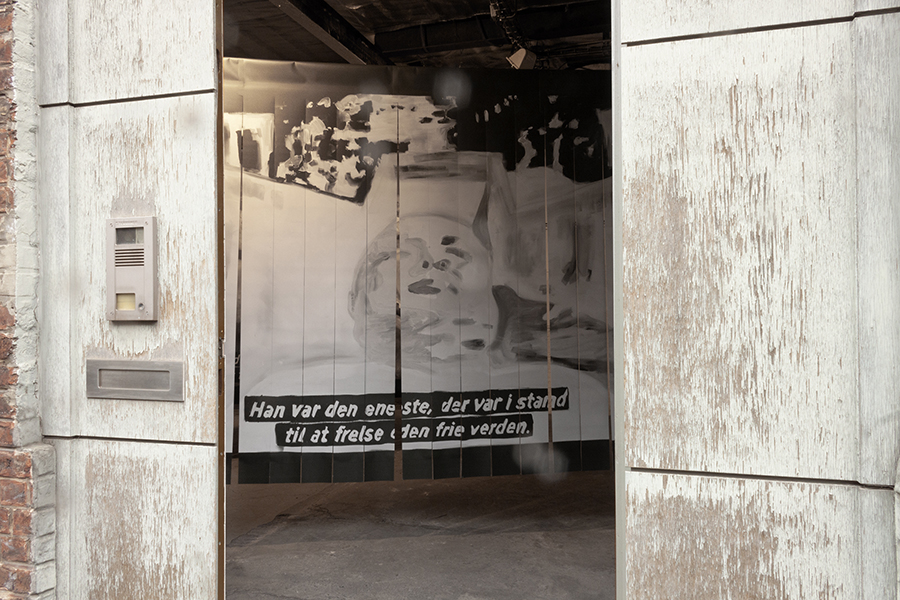

If You Are Going Through Hell, Keep Going. Churchill functions as both a conceptual and physical threshold, positioning viewers within the interplay of propaganda and persona construction. Installed as an entry piece, this triptych—printed on vinyl strips reminiscent of an industrial entryway—depicts Winston Churchill, headfirst and face up, sliding down a waterslide in the south of France. A seemingly lighthearted moment, captured by a film crew, becomes a curated image of resilience and approachability, signaling the construction of myth even in leisure.

Requiring viewers to pass through Churchill’s carefully framed persona, the installation underscores the serialized nature of propaganda, exposing the mechanisms by which historical figures are mythologized. Danish subtitles reading, “he was the only man who was able to save the free world,” reinforce the gap between reality and representation, while the title, referencing a widely misattributed Churchill quote, further amplifies the instability of historical narratives. Both threshold and thesis, If You Are Going Through Hell, Keep Going. Churchill frames an inquiry into the enduring power of visual mythology, revealing how political influence is shaped, circulated and consumed.

“If You Are Going Through Hell, Keep Going.” Churchill, 2017-2019

(panel I)

Inkjet on vinyl

120” x 84”

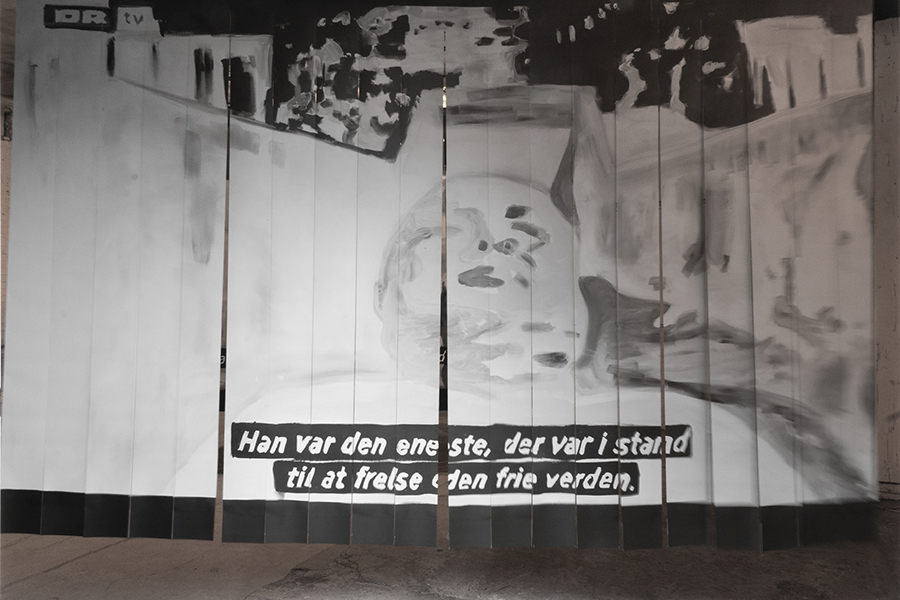

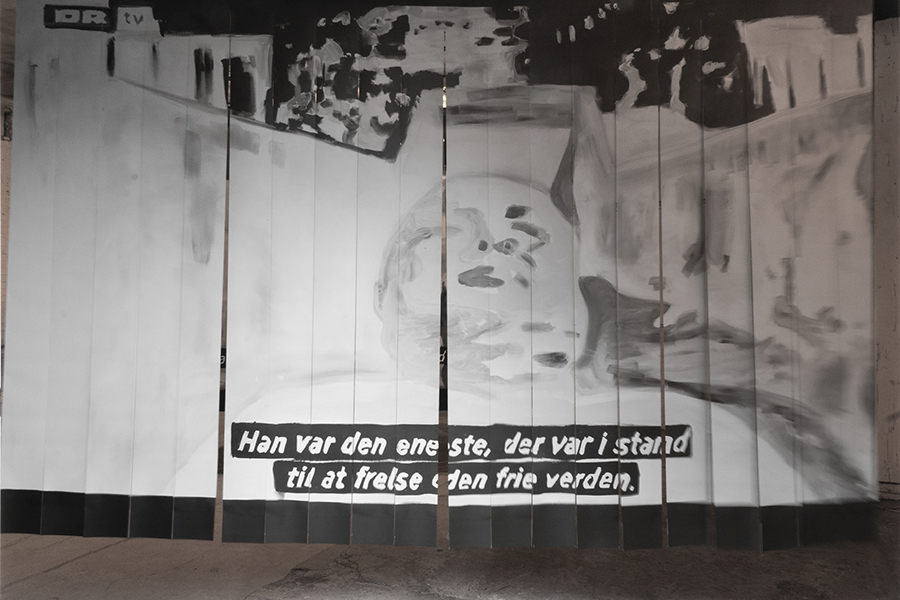

“If You Are Going Through Hell, Keep Going.” Churchill, 2017-2019

(panel II)

Inkjet on vinyl

120” x 84”

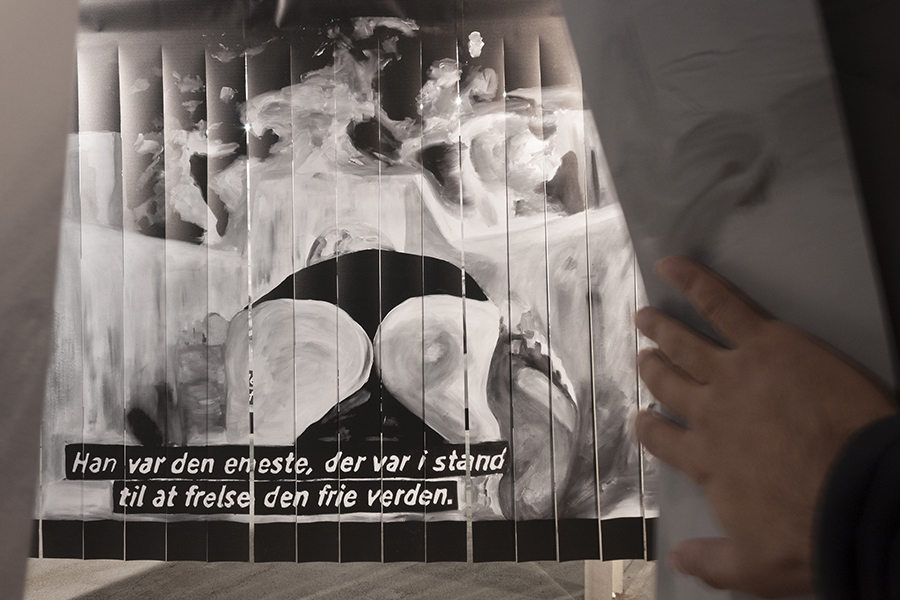

“If You Are Going Through Hell, Keep Going.” Churchill, 2017-2019

(panels II and III)

Installation view

Mann Ist Mann, 2017-2019

Lead oil paint on canvas

84” x 124”

Mann Ist Mann examines the performative nature of power and the fluidity of identity within political frameworks. The title—meaning “a man is a man”—echoes Bertolt Brecht’s notion of individuals as interchangeable within ideological systems, particularly in military or authoritarian structures. This idea resonates through the painting’s depiction of Tsar Nicholas II in a moment of staged playfulness, a carefully curated image that underscores the theatricality embedded in political authority.

The Tsar’s direct gaze, breaking the “fourth wall,” alludes to Brechtian strategies of exposing constructed narratives—techniques later weaponized by figures like Vladislav Surkov, a former theatre director who shaped contemporary Russian political myth-making. By juxtaposing historical and modern power structures, Mann Ist Mann critiques the manipulation of public perception, revealing how authority is performed, reinforced and ultimately interchangeable within ideological systems.

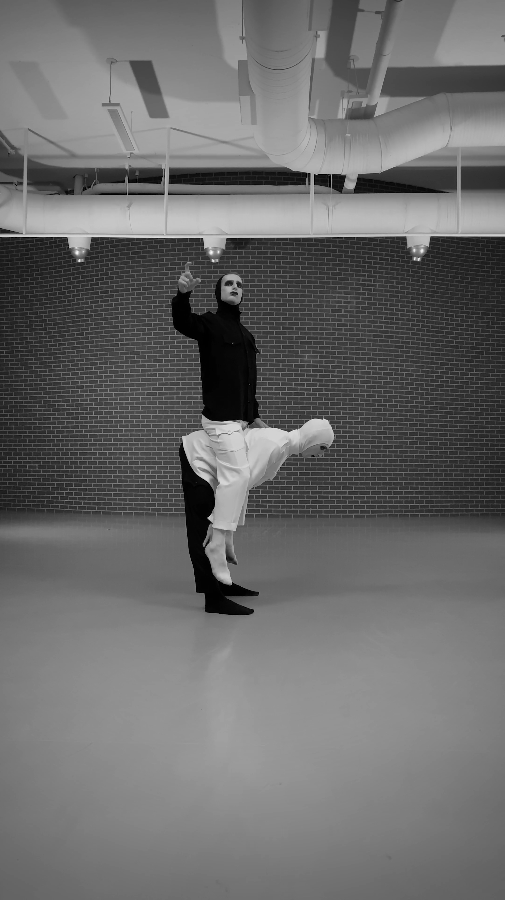

2019

Five channel HD video | 6m 30s

Choreography:

Emmalena Fredriksson

Music Composition: François Houle

Cello: Marina Hasselberg

Dance:

Matthew Wyllie and Aiden Cass

Rehearsal is a five-channel video installation examining identity, repetition and the conditioning forces that shape selfhood within systems of power. Featuring two contemporary dancers, choreographed in collaboration with Vancouver-based choreographer Emmalena Fredriksson, the work unfolds through five iterative variations of a musical piece originally composed for Bertolt Brecht’s 1926 play Mann ist Mann. The score was reimagined through collaboration with composer François Houle and performed by cellist Marina Hasselberg, expanding its sonic and rhythmic dimensions. Structured yet mechanical, the dancers’ movements embody a gradual dissolution of self, mirroring the tension between autonomy and control.

The multi-channel format amplifies this cyclical fragmentation, reinforcing the instability of identity under imposed structures. By framing the dance as an ongoing rehearsal, the work exposes the mechanics of conditioning, revealing how repetition, discipline and performance reinforce ideological influence.

2017

-Lead oil on canvas

136” x 84”

-MP3 sound

20s

Sellers examines the convergence of propaganda, marketing, and psychological influence through an anamorphic portrait of Joseph Goebbels and an accompanying sound piece. The work highlights ideological parallels between Goebbels, the Third Reich’s Minister of Propaganda, and Edward Bernays, the pioneer of American public relations and nephew of Sigmund Freud, revealing their shared strategies of mass persuasion.

The sound component features a 20-second audio clip of Thea Rasche, a 1920s German pilot and media sensation whose public image—shaped by Bernays—promoted consumer ideals like self-expression through dress. This entanglement of propaganda and consumer culture is further emphasized by Goebbels’s distorted portrait, shifting with the viewer’s position to underscore the subjectivity inherent in ideological influence. Referencing Bernays’ Propaganda (1928)—a foundational text in modern advertising—the installation critiques how psychological tactics of persuasion continue to shape public consciousness, exposing the mechanics of influence embedded in media and political discourse.

2017-2019

Lead-base oil paint on canvas, custom-made wooden frame

40” x 46” x 4”

Amusement Park, 1926 interrogates the disturbing intersection of nostalgia, violence, and racial spectacle in American history. At first glance, the work presents a delicate, washed-out Impressionist rendering of an amusement park, framed in a classicized colonial style. Upon closer inspection, hooded KKK figures occupy the Ferris wheel, while embers smolder on the ground—a haunting allusion to racial terror. Based on a 1926 photograph by Clinton Rolfe documenting a KKK amusement park in Colorado, the piece juxtaposes aesthetic innocence with systemic brutality, exposing how visual nostalgia not only veils historical atrocities but also reinforces their place within cultural memory.

The custom frame, referencing French colonial design and subtly incorporating miniature nooses, heightens this tension, embedding symbols of beauty and brutality within a single cultural artifact. By merging idyllic imagery with latent violence, Amusement Park, 1926 critiques how histories of racial terror are aestheticized, sanitized, and repackaged within collective consciousness. The work compels reflection on how the past lingers within the present, revealing the uneasy ways in which systemic violence is not just remembered, but continually reimagined and reinscribed in visual culture.